How much money do I need to start? How much can I lose? How do I make my first stock purchase? Which brokerage is best? Some basic advice for first time stock buyers.

Buying Your First Stock

Buying your first stock can be a daunting prospect. If you are thinking of moving beyond the world of mutual funds and ETFs into the scary but rewarding world of individual stock ownership, here are some answers to a few of the questions that newbie investors often have.

How Much Can I Lose?

I feel the Wall Street machine does a poor job of warning investors about the full risks they face. This is completely understandable as most investment professionals have something to sell and it would not be good for business to scare off your customers with tales of gloom and doom. Fortunately, I am under no such constraints, so let me do my best to scare the living daylights out of you!

Historically, the stock market has offered the best long term returns of any of the easily investible asset classes. Over the past 100 years or so, stocks have risen by about 5% per year over inflation. But it’s no free ride. There’s a reason stocks offer some of the highest rewards for your investing buck. It’s because they also come with some of the highest risks.

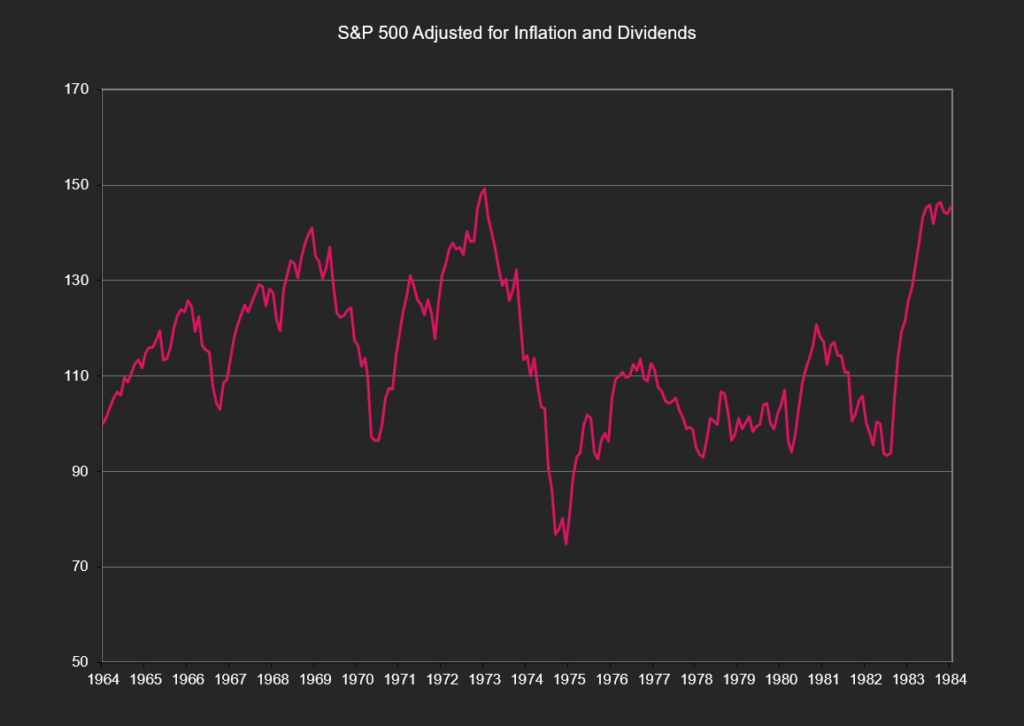

In the past few decades we’ve seen three occasions in which stock prices dropped by 40% or more peak to trough. If you had been unlucky enough to be invested in the NASDAQ in 2000, you would have seen 75% of your wealth evaporate. In the crushing bear market of the 1970’s, small cap investors also lost 75% of their money and in the Great Depression, the market dropped 86% from top to bottom. What’s more, stocks can go down and stay down for a long time. It took 25 years for the market to regain its footing after the stock market crash of 1929. In Japan, it wasn’t until 34 years later that the Nikkei index regained the level it first reached in 1990.

Here’s an example of what a bear market can look like…

Unless you face an untimely demise, it is almost a certainty that you will face one of these painful bear markets (and quite possibly more than one) during your investment career. If you’re young, the good news is that you probably don’t have to worry too much about all of this. Your portfolio is small and any major drop in prices just means you get to put every extra dollar of savings to work at much reduced prices. But if you’ve been around the block a few times, the risks are much greater. The only way to properly deal with them is to make sure you are prepared beforehand. Once the decline happens, it is too late. There is no sign that lets you know how much longer or further a stock market drop will go. There is no way to effectively get out once the bear market has begun because you never know if it is the beginning of a years-long mauling or just a more temporary “correction.” And there is no way to reliably get back in at the bottom because the trough is only apparent after stock prices have moved back up significantly.

For first time investors, my advice would be to plan for at least a 50% drop in stock prices. Add up the amounts you have exposed to the stock market, including any equity mutual funds, exchange traded funds, company stock and whatever amount you are planning to commit to your new stock trading adventures and then divide that in half. Would you be okay with losing that amount of money? Assume that the process will be a long, painful one and that prices will stay down for years. Could you stomach that kind of loss? The time to think about this is now, not after the drop has happened. Many investors will get flushed out by the next big, bear market. Make sure you’re not one of them by preparing beforehand.

I have a good friend who always splits his portfolio 50/50 between an interest bearing cash account and stock market investments. That way, if the markets drop in half, he will have only lost 25% of his money. That’s the ratio that lets him sleep well at night. Before making your first stock investment you need to figure out what your pain point is. You can’t close the door after the horse has left the barn, you need to do it now.

This is a weighty decision and, quite honestly, an uncomfortable one to make and the answer is going to be different for everyone. If you are struggling with figuring out the right balance for you and your situation, this is where a good financial adviser can be a big help.

There are some more elaborate ways of hedging your downside risk, put options, funds that sell stocks short and other more esoteric approaches, but these are all expensive. For most investors, a simple asset allocation strategy, putting a healthy portion of their portfolio into safer assets like cash, GICs / certificates of deposit, money market funds or short-term government bonds is the most sensible approach.

In other words, don’t put all of your eggs in one basket. Or, if you do (I do) fully understand the implications of that cowboy approach.

If the market is high right now, should I wait to invest?

Surprisingly, my answer to this would be “no”. It is very difficult to time the market. While prices may be high, they can stay that way for years at a time. And the market can suffer a big drop even when prices seem reasonable. I would decide on how much you are going to allocate to stocks, understanding that there is always the chance that markets could take a big plunge and then buy your stocks when you have the money and when you find something you want to buy. Trying to do otherwise will drive you nuts.

How much do you need to get started?

Not much. Even if you only have a few hundred dollars to spare, you can still open a discount brokerage account. Keep adding to the account as money becomes available. Once you’ve built up your first thousand, you can start thinking about buying your first stock.

The average discount broker charges a $10 commission to place a trade, regardless of the number of shares involved. You could buy $1,000 or $10,000 worth of stock and you’d still pay the same $10. If you are placing an order to buy $1,000 worth of a stock and paying a $10 commission for that trade, then you are paying a 1% commission. As long as you’re buying with a reasonably long-term focus then that seems to be a reasonable price to pay to me. I hold my stocks, on average, for about a year and a half each. If I were to pay a 1% commission to buy and 1% to sell, then that means I’d be paying commissions of about 1.5% every year on my portfolio of stocks, if I were to put $1,000 into each idea.

That is equivalent to the fees charged by the typical mutual fund. So as a very general guideline, I’d suggest that perhaps $1,000 should be the minimum you put into each of your new holdings. If you only have $1,000 then just buy one stock. Take the time to learn as much as you can about that company and then follow it closely. Once you have your next $1,000 saved up, buy yourself another stock. And so on. After you’ve accumulated half a dozen different stocks, you might want to start increasing the amount you hold in each one.

The point being, you don’t need to be a millionaire to invest in the stock market. You can get started with as little as $1,000 and then gradually build over time from that modest beginning.

How Many Stocks Should I Have In My Portfolio?

If you only have enough money to buy one stock, then start with one. But if you’re starting with a larger sum at your disposal, how many stocks should you be aiming to buy?

The more stocks you own, in general, the more diversified and the less volatile your portfolio will be. But there is a trade off. At any given point in time there are only a limited number of deeply undervalued stocks out there in the market. Adding additional stocks to the portfolio, simply to broaden your diversification will probably mean adding stocks that may not be as promising as the ones you already own. Many of the most successful investors run surprisingly concentrated portfolios containing only a handful of very carefully chosen investments. You want your portfolio to be packed with your very best ideas, not your second tier choices. As well, the more stocks you own, the more difficult it is to pay proper attention to each one.

On the other hand, individual stocks, especially smaller ones, can be very volatile. The price could conceivably fall to zero, wiping out your entire investment. Or it could double or triple in price. If you are investing small sums, that kind of fluctuation is alright. But if you are dealing with a larger portfolio, you’re going to prefer to have your bets more spread out so that the winners will balance out the losers and keep your portfolio running on a more even keel.

I’ve generally found 10-15 stocks to be the sweet spot for me. There will be the occasional blow-up and also the occasional home run but overall, this number of carefully chosen, small cap stocks from a variety of industries and sectors, helps keep the turbulence to a minimum.

Give Me Shelter

Before getting started, you’ll need an account to do your trading in. I’d highly recommend setting up a tax-sheltered account of some sort if you’re able to. Not only will your money grow tax free but the record keeping is much, much simpler. Investing outside of a tax-sheltered account means having to calculate adjusted cost bases, capital gains and losses and having to deal with sometimes complicated tax planning around the timing of buying and selling decisions. Much better to make life easy on yourself and keep your stock trading confined to a tax-sheltered account.

For my Canadian readers, that means a TFSA or an RRSP. There’s been a lot of ink spilled over the advantages and disadvantages of each. In the end, it usually doesn’t make a great deal of difference. With an RRSP you get a tax rebate up front, but you have to pay tax when you ultimately take the money out again. With a TFSA there is no tax rebate for your contributions but no tax owing on your withdrawals either.

Full service broker vs. discount broker

The next decision is whether or not to go the DIY discount brokerage route or sign up with a full-service broker or investment adviser who can offer more advice and support. All of the major banks in Canada have a discount brokerage attached to them where you can set up an online trading account, whether it be an RRSP, a TFSA or a regular, taxable, “cash” account. There is really not much that sets one apart from the others. They might offer different bells and whistles but they all perform the same basic function of accepting and placing your buy and sell orders. Their commission rates are also all very low and competitive with each other. Simply choosing whichever brokerage is associated with the bank you do your banking with will keep life simple.

If you are completely new to the game of investing, you might want a more full-service option, at least to begin with. This is the route I took when I first started out. I opened an account with a big, full-service brokerage and accepted the 3% commissions they charged as part of my tuition. After the first year of hand holding, I transferred my money to a discount brokerage and continued on from there.

A good fee for service financial adviser and an accountant can also be useful additions to your arsenal especially if you have a larger account or a more complex financial situation.

If you’re young and you don’t have a large portfolio or a lot of resources at your disposal, then setting up an online account at one of the new upstart independent discount brokerages might appeal. If you don’t mind making a few mistakes along the way, you can certainly go the full-bore DIY route.

Once you’ve got a dedicated account set up and have the support network you need in place, you’re ready to start buying stocks.

There are a myriad number of different ways you can approach investing and stock selection. The hot-tip-from-your-dentist approach is a commonly employed one, although probably one of the least effective. I’d personally advocate a value-oriented strategy like the one that I use. Exploring this site in depth, you can see how I personally go about selecting stocks. There are also a wealth of other resources you can use to generate ideas: newspapers, magazines, online financial sites, newsletters. Find a source or an approach that resonates with you.

Start slow

Start slow. There are likely going to be some mistakes and false starts to begin with. Take the pressure off by beginning with a small portion of your portfolio and add more to it over time. If you are new to the game, start with a handful of stocks that you have the time to properly monitor and slowly add to your holdings as you gain experience and confidence. There is no rush. Building a portfolio is a long-term proposition. Most people are saving money for a retirement that is years away. Even if you’re nearing the end of your career, if you live a long and healthy life, you may still have several decades of investing ahead of you. Practice walking before breaking into a run.

Trade Execution

If you’ve finally got everything set up and are ready to buy your first stock, it would be a big help to have a buddy beside you who has done this before and can walk you through the process. Those first few trades can be nerve-wracking. What if you press the wrong button or enter the wrong price? Be careful the first few times you do it and double check all your numbers. While trading online is fast and convenient, you may want to place a telephone order those first few times so that you can deal with a real, live person who can walk you through the right procedure and catch any errors that you might make.

One of your first decisions will be whether or not to use a market order or a limit order. For the big, large cap stocks that trade millions of shares a day, a market order is probably fine. This type of order means that you will just accept whatever the current asking price is for your stock. For smaller, less frequently traded stocks, this can get you into trouble though. If the stock has been trading at around the $2.00 mark but for whatever reason, there is no one out there currently who wants to sell the stock at that price, then your order could get unexpectedly filled at a much higher price.

To avoid this, I use limit orders for most of my trades. A limit order means you specify the price you are willing to buy or sell the stock at. For instance, if the stock has been trading around $2.00 and the current bid is $1.95 while the current ask is $2.05, that means someone else is offering to buy the stock at $1.95 and someone is willing to sell at $2.05. You could enter $2.05 as your limit price and get filled right away (provided the seller was selling the number of shares you wanted) or you could enter something lower, $2.00 say, or $1.96. You’d then just let the order sit and check back in periodically to see if it had been filled. You might check in a few hours later and see that it had not been filled and, in fact, the current bid had moved up to $2.01. Someone else has outbid you! At this point, you could change your own order to $2.02 or $2.05 or leave it as is in case the stock price comes back down.

Think of the whole process as very akin to haggling at a bazaar except that you are doing it electronically instead of face to face. Like haggling, it is a fine art and there is no right way to go about it. I have to admit, it is my least favourite part of the whole investing process.

When you put in a limit order you can specify if it is good for the day, in which case your offer will expire at the end of trading that day, or if you want to keep the order out there for a few days or weeks to see if you get any takers. If you leave the order open for more than a day, then you will be charged the commission for each day that part of your order is filled. If you put in an order to buy 1000 shares and 100 are filled on Monday, 600 on Wednesday and the final 300 on Thursday, then you will pay your standard commission ($10, for example) 3 times.

Canadian stocks whose price is under $1.00, are traded in lots of 500 shares each. While you can buy shares in smaller, uneven increments, it can be harder to find a buyer or seller to match your order. You may end up having to place a market order to unload the stub amounts and therefore may not get as good a price. For stocks trading over $1.00, the lot size is 100 shares. For highly priced stocks, this can mean a significant chunk of change. In this case, if you’re investing smaller amounts of money, you may be forced to buy in increments of less than 100. But for larger stocks, with heavier trading volume, this probably won’t be as big a deal.

Just go for it!

Hopefully I haven’t scared off all my neophyte readers by now. One of my main goals with this blog is to lure investors away from the siren song of the fund companies and get them to start selecting and buying their own individual stocks. As with anything, it gets a lot easier with practice. Go in with your eyes wide open, understanding the risks you face but also the potential rewards. Take things slow. Make sure you have the backup and support you need. When you’re ready, I hope you’ll take the plunge. If it helps, check out this post, if you haven’t already… If a monkey can do it, so can you.