Part 4 in a series of tutorials on value investing: The ratios and formulas I use to find undervalued opportunities.

Part 1: My Investment Philosophy

Part 2: The General Store

Part 3: The Investor’s Toolkit

Part 4: Building a Valuation Framework

Part 5: Hitting The Books

Part 6: When To Sell

Red Fish, Blue Fish

There are a bewildering variety of companies listed on the stock market. There are technology superstars, blue chip stalwarts, young companies with fresh, new ideas and former industry leaders well past their prime. Retailers, manufacturers and biopharmaceutical start-ups. Global shipping companies, auto parts distributors and fast food franchises. How does one even begin to make sense of this chaotic jumble of opportunities?

For starters, I simply discard from consideration many of the companies that make up the market. Entire sectors of the market get the cold shoulder from me. The resource industries: mining, oil and gas and forestry tend not to lend themselves well to my sort of earnings-based analysis. Certainly, exploration companies are beyond my ken. I don’t have the expertise to know if a patch of moose-pasture in Saskatchewan has a high-grade vein of gold lying under it or not. Even the resource production companies give me problems; their fortunes are closely tied to future commodity prices and I have no particular insight into what the price of zinc will be in a year’s time. I do invest in the companies that service the resource industries, though. These seem a bit more amenable to my style of analysis.

The banking and real estate sectors also get a pass from me. Banking is too much of a black box for my liking and real estate companies are priced more on the asset value of their property holdings than they are on the earnings (if any) they might be generating. I ignore biotech as well. I don’t have any idea which experimental drugs may successfully run the long gauntlet of clinical trials to gain ultimate FDA approval, and which will not. Utility companies generally carry far too much debt for my liking.

Any company with a long history of losing money gets a pass from me. My analysis typically centers around a company’s earnings, or more accurately, what I expect its future stream of earnings to look like. And to help determine this, I look to its past record of profitability. Companies that have never made a profit don’t lend themselves very well to my sort of analysis. I know where my strengths lie and it is not in being a future visionary, assessing the impact of paradigm-shifting new technologies or the strength of a company’s network effects.

My analysis is often much more grounded than that. Is the company making money? How much? And how much do I have to pay to get a piece of that action? This means I miss out on many of the hottest investment fads of the day. The glamour or story stocks that make for exciting coffee shop chatter and speculation rarely show up on my screens. And that’s just fine. My stodgy old portfolio has provided me with plenty of excitement over the years. A construction company may not have the sparkle and shine of a biotech company working on a break-through drug, but when the stock triples in value, it can still get the heart racing.

As a final part of my screening process, I apply a basic test of financial strength. I want total net debt to be less than five times annual earnings. If a company is more highly leveraged than that, I am generally not interested. It may be a great company otherwise but if it’s carrying a heavy debt load, I’d rather take my investment dollars elsewhere.

Apples To Oranges

Even after this extensive winnowing process, there are still a dauntingly wide array of companies to deal with. How do I compare a global car company to a small, regional chain of coffee shops? Or a rapidly growing software company to a struggling newspaper publisher? I need a common valuation framework that I can use to measure and compare these disparate businesses. Something that will let me narrow the playing field and lead me to the companies that have the potential to offer me the most value for my hard-earned investment dollars.

One approach would be to simply buy the stocks that had the lowest p:e ratios, with no effort to discriminate between the good, the bad and the ugly. While not terribly sophisticated, it’s been shown that this approach would have been surprisingly successful over time, outperforming the overall market by a percentage point or two a year. With this approach, you’d end up owning a lot of crappy companies, but every so often one of them would manage to pull a rabbit out of its hat and the resulting gains would make up for all the losses on the ones that didn’t fare so well.

However, holding on to a portfolio like this would be hard, especially when the market turns south and your portfolio of dogs starts to look increasingly feral. You’d be at risk of losing your nerve and bailing at precisely the wrong time. What’s more, by concentrating on only the lowest tier of the market, you’d be ignoring a lot of interesting and potentially lucrative opportunities higher up the quality spectrum. And by higher quality, I mean companies with higher expected future growth. A market strategy that leaves room to invest in more highly priced, higher quality companies will lead to a more diversified and balanced portfolio and one that will likely perform better in the end, with less stomach churning volatility along the way.

The key to a diversified value investing approach is to not just focus on the cheapest of the cheap but instead to effectively match up price and growth, buying the best combination of those two factors that you can find. A high growth company can be an excellent value at the right price but so can one that is not growing at all. It’s not the underlying growth or lack thereof that makes a good investment, it is the price you pay for that growth. A good valuation yardstick will take growth into account and let you find value priced stocks up and down the quality spectrum.

Putting A Price On Growth

So we need to move away from the simple low p:e approach and add some nuance to the proceedings. If you survey the normal spread of p:e ratios on the street, you’ll find that the p:e ratios displayed by companies with different growth rates follow a very logical progression. Generally speaking, the higher the expected future growth rate, the higher the p:e ratio. Investors are looking ahead and basing their pricing decisions not on current earnings but on their estimate of future earnings. The more earnings are expected to grow in the future, the higher the price the investor is willing to pay today.

But how far into the future are investors willing to look? 5 years? 10? 20? The longer you are willing to extrapolate out current growth rates, the more earnings will compound and grow and the more you’d be willing to pay today to get a piece of those anticipated future profits. Take the example of a company growing at a rate of 15% per year. At that rate, earnings will double in 5 years. In 10 they will quadruple and in 15 years, if nothing derails this juggernaut, earnings would have grown by a factor of 16. If you were to base your earnings expectations on that 15 year projection, you’d expect to see a current p:e ratio that was orders of magnitude higher than that of a company with a more pedestrian outlook.

And indeed, that is what you sometimes see in the most popular growth stocks of the day. Investor’s willingness to extrapolate current above trend growth many years into the future explains why some of the popular stock market darlings can sometimes hit astonishing triple digit p:e ratios.

But overly optimistic investor expectations are usually brought back down to earth at some point and horizons are shortened to a more realistic time frame. As expectations are reduced, the p:e ratio drops, and excitable investors shift their attention elsewhere.

The reality is that the future is highly unpredictable. Company fortunes wax and wane. Economic trends shift. Investor sentiment rises and falls. Any future predictions are going to be rough estimates at best. Trying to predict growth rates too far out into the future is a fool’s errand.

In my experience, five years seems to be the sweet spot for stock market prognostication. This is a reasonable time frame to use when making your growth determinations and seems to be the time frame that is most commonly reflected in the normal spread of valuations that you see in the market (ignoring the occasional outburst of market euphoria). Beyond 5 years, the crystal ball starts to get increasingly cloudy.

Where growth is concerned, there is a strong tendency towards reversion to the mean. Weak companies are heavily incentivized to get their act in gear. New management is put in place, painful restructurings are done, new markets are explored. Sometimes it’s just a matter of the economic tides changing direction. Likewise, any run of strong growth is always at risk of getting cut short by new products, new competitors, saturated markets or changing consumer tastes. Nothing on Wall Street is forever and so I assume that after a period of about 5 years any currently observed above or below trend growth will tend to converge back to the long-term market average.

This baseline assumption makes my job of valuing stocks a lot easier. I do need to factor growth expectations into my calculations, but I don’t have to tie myself in knots trying to figure out what might happen 10 or 15 years down the road. The next few years is all I can really hope to see with any degree of clarity. Beyond that, current high-flyers may flame out and come crashing back down to earth while market laggards can overcome their challenges and go on to become the future market darlings. I’m looking into the middle distance, about 5 years out, and basing my valuations on that outlook.

The 5 Year P:E Ratio

The simplest way to do this is to simply base our p:e ratio not on current earnings, but on what we expect the company to earn five years down the road. Doing this, elegantly combines our earnings estimates and our growth rate expectations into a single number that we can then use to compare different companies with very different growth prospects.

Setting a 5 year time limit on your forecasting ability puts an important brake on the natural tendency to get caught up in the latest market success stories. Equally important, it forces you to take a second look at companies that are currently struggling. Five years later, the success stories may be facing struggles of their own and the weaker companies may be on a roll.

To calculate the 5 year p:e, you divide the stock’s current share price by what you expect its earnings per share (EPS) to be 5 years in the future. And to calculate those future earnings you multiply the current earnings by (1 + annual growth rate) 5 times. If you were using exponential notation, you’d write this as (1 + growth rate) ^ 5. Putting this all together yields the following formula…

5 Year P:E = Current Share Price / (Current EPS x (1 + growth rate) ^ 5)

A high growth company with a share price of $60, for example, and earnings of $2 a share, growing at 15% per year would have a high current p:e ratio of 30 ($60/$2) but a 5 year p:e ratio of only 15 because of the growth in earnings in the interim. $60 / ($2 x 1.15 ^ 5) = 15.

Conversely, a company that isn’t expected to grow at all would have a 5 year p:e ratio that was the same as its current p:e ratio because the earnings part of the equation hasn’t changed. As we raise the growth rate above zero, our 5 year earnings estimates increase and as a result the 5 year p:e ratio declines.

Normally, we’d expect a high growth company to have a present day p:e ratio that was about twice as high as its no growth competitor. If the no growth company was trading at 15 times earnings, we’d expect the high growth company to trade at 30. Which makes it more difficult to compare the two scenarios. What if we found a high growth company trading at a p:e of 20 and a no growth company trading at a p:e of 12? Both are trading at a discount to what we might expect and so both might offer some value, but which is cheaper? It’s not immediately obvious.

If instead we calculate the 5 year p:e in both cases, the p:e ratio of the no growth company won’t change; it will still be 12, but the p:e ratio of the high growth company will drop in half, from 20 to 10 (because in 5 years we expect the earnings to have doubled.) Now we can more easily compare the two situations and decide that the high growth company offers the better value. (10 being less than 12.)

The 5 year p:e ratio puts all companies, irrespective of their varying growth outlooks, on an even footing. Current p:e ratios are expected to be different, as investors price in different rates of expected future growth. 5 year p:e ratios, on the other hand, already incorporate those growth expectations and so should all be equal. Theoretically that is. But the market may have a very different outlook on the future than you do and so it’s pricing of a stock will vary from yours. Here’s where the opportunity lies. Assuming that your interpretation is the correct one, if you find a stock whose 5 year p:e ratio is significantly below average, then that is an indication that the company may be mispriced.

At this point, it’s time to roll up your sleeves and get to work. Other investors are not stupid, and it may be that it is not the stock that is mispriced, it is your expectations that are way off base. You need to do your research and double and triple check your assumptions. If you are still confidant in your own estimates after doing your homework, then it’s time to bet on the home team. Value investing is about identifying those situations where your outlook diverges significantly from the herd and then betting that you’re right and everyone else is wrong. It happens more often than you’d think.

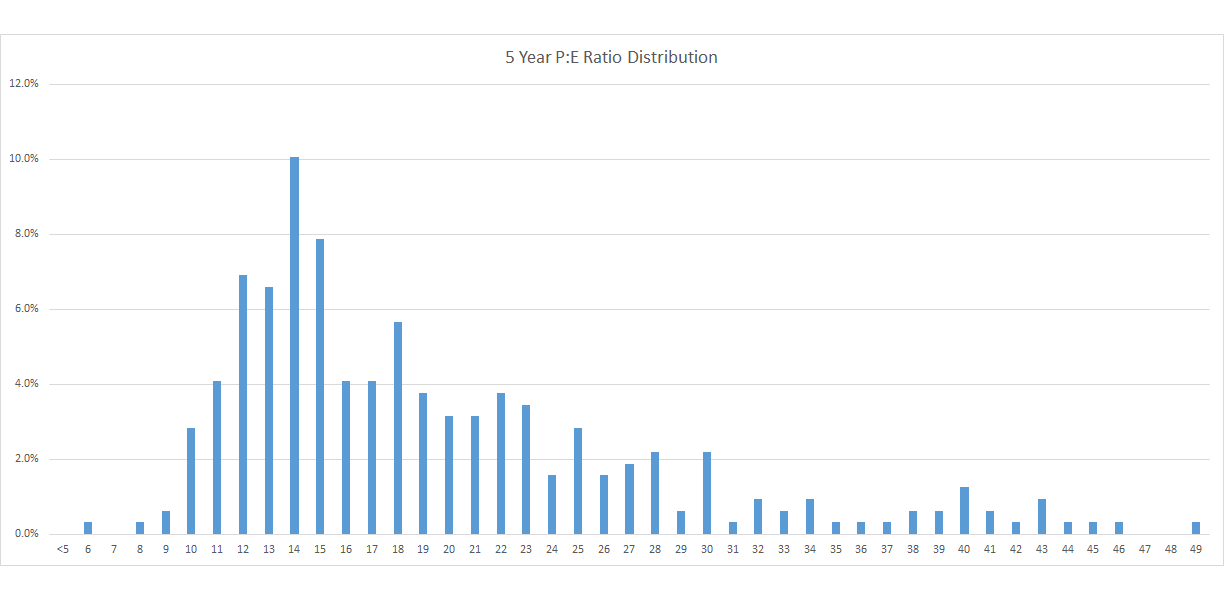

I recently did one of my periodic reviews of the market. I went through a list of about 400 small cap stocks, analysing them and forming opinions as to their estimated earnings and growth rates. With these two pieces of information in hand, I could calculate the 5 year p:e ratio for each stock, using my own earnings and growth assumptions. I could then graph these numbers on a histogram to see how the 5 year p:e ratios were distributed.

As you can see, in this market environment, the 5 year p:e ratios tended to cluster around the 14 mark. By zeroing in on those companies that were trading significantly below that number, ideally with 5 year p:e ratios in the single digits, I could pinpoint value-priced opportunities that the market may have overlooked.

The 5 year p:e ratio gives us a quick and easy tool that we can use to sift through the market looking for cheap, undervalued situations. Because it already incorporates an assessment of growth within it, we can once again resort to simply searching for stocks with the lowest p:e ratios and we don’t have to worry that we’ll just end up with a bunch of deadbeats in our portfolio. A high growth company that has been underpriced and a low growth company that has been equally underpriced will both have similarly low 5 year p:e ratios and will both get called to our attention as we search the market for bargains.

One very effective investing approach, especially if you’re a more casual investor who might only be able to devote your attention to the markets on a more sporadic basis, would be to search out those low 5 year p:e opportunities as time permits. For every company you examine, you’d have to calculate its current, baseline earnings (more on that in the next chapter in this series) and form an opinion as to its expected future growth rate. With those two pieces of information in hand, you could calculate its 5 year p:e. When you found a stock with an unusually low ratio, you’d give it a thorough going-over. If, after your investigations, you remained undeterred, you could compare it to the other stocks in your portfolio. If it had a significantly lower 5 year p:e ratio than a stock you already owned, you’d sell the old stock and buy the newcomer.

If you were continually optimising your portfolio for value in this way, you’d have a winning portfolio that was primed for success and very likely to outperform over time.

For a look at how using the 5 year p:e ratio to value stocks might work in practice you can check out my Portfolio Review blog post from September 2023, where I use this tool to examine my own portfolio of stocks.

Fair Value

After playing around with 5 year p:e ratios for awhile, you’ll start to get a sense for what a normal ratio might be for the kinds of stocks you’re looking at. As the market rises and falls, this number will rise and fall as well. Whatever the level is currently, you’re looking for stocks that are trading significantly below that, hoping they will narrow the gap over time. The level you expect a stock to trade at, based on your analysis, is known as its fair value or intrinsic value and the discount to this value is known as the margin of safety. The idea behind the margin of safety is that the discount you’re buying in at provides a cushion in case things don’t turn out quite as well as you expected.

Generally speaking, you want as big a discount as possible in the stocks you buy. I try to shoot for a 40% discount in my own trading. The bigger the discount, the bigger the potential profit. The valuation gap acts like a magnetic force, inexorably pulling your stocks higher. It often doesn’t happen right away. The valuation gap between your stocks and the rest of the market can be maddeningly slow to close at times, but if you’re patient, the odds are good that you’ll ultimately be rewarded.

The Expected P:E

The 5 year p:e ratio is not part of the regular investment lexicon. If you try using the term in conversation, no one will know what you’re taking about. If you’re reading the financial press or analyst reports, you won’t find any mention of a 5 year p:e. Investors do frequently use a 5 year time horizon in their modelling, but they then work backwards from that to figure out what price or p:e ratio they’d be willing to pay today to allow for the future growth they’re expecting to see 5 years down the road.

In order to emulate this approach, we need to focus on the here and now. This means that our expected p:e ratios are once again going to be all over the map. High growth companies will have high p:e’s and low growth companies will have low p:e’s. We’re attempting to price in the rate of expected future growth into today’s stock prices and the range in p:e ratios reflects that. The degree to which those present day p:e ratios are elevated or depressed relative to the market average is directly related to the degree to which earnings are expected to grow or contract also relative to the market average.

Specifically,

Expected P:E = Market Average P:E x (1 + growth rate) ^ # years / (1 + market average growth rate) ^ # years.

Where growth rate is the expected future growth rate of the company we’re looking at, # years is the number of years we expect that growth to continue, and the market average growth rate is the expected growth rate of the average stock.

To solve this formula, we need to know the average rate of growth of the market. Over the past 60 years, the market has grown by around 6% per year over inflation, so that’s the number I’m going to use. The average p:e ratio of the market was similar at the start and end points of that series so by extension, corporate earnings would have also risen at an average rate of 6% per year.

If we use the same 5 year look-ahead period that we used for the 5 year p:e, and fill in our 6% number for the market average growth rate (1.06 ^ 5 = 1.34), we can simplify the formula above to…

Expected P:E = Market Average P:E x ((1 + growth rate) ^ 5) / 1.34

Next we need to know what the average p:e of the market is. This is surprisingly difficult to figure out. 10 different sources will define this number 10 different ways. It depends what market you’re talking about (the S&P 500, the Russell 2000, large caps, micro caps, etc.). It also depends on how you calculate the number (average, median, equally weighted, market cap weighted). Finally, it depends on what earnings you are using in your calculations (as reported earnings, operating earnings, forward earnings estimates, 10 year average (CAPE) earnings). Whatever number you choose has to be relevant to the kinds of stocks you’re looking at. If you’re focused on the micro cap sector, the average p:e of the S&P 500 may not be particularly useful.

This is where your own 5 year p:e calculations really come in handy. If you have enough observations under your belt, you can calculate the average 5 year p:e of the stocks you’ve been looking at. (Or better yet, the median, as averages tend to get skewed by outliers. Or even better, the high point in a distribution graph like the one I displayed in the 5 year p:e section above.) At the 6% average rate of growth of the market, earnings would grow by 34% over 5 years, so to convert an average 5 year p:e back to the present, we just need to multiply by 1.34. (Note: this only works for market averages. You can’t multiply the 5 year p:e ratio of an individual stock by 1.34 to get it’s current expected p:e. For individual stocks you have to use the formula above.)

If you don’t have a good cross section of your own observations to work with, you can substitute some sort of market average that you’ve culled from another source, just be aware that this number may not be perfectly representative of your own universe of stocks.

Let’s run some examples. Over the last 20 years the median p:e of the New York Stock Exchange has fluctuated around the 20 mark. At times, it’s gone far above and below that number, but for argument’s sake let’s just assume we are sitting around that level now.

In this sort of market environment, what would we expect the current p:e ratio to be of a rapidly growing company growing at 18% per year?

Expected P:E = 20 x (1.18 ^ 5) / 1.34 = 34

Sounds about right. We think it’s got a good stretch of growth coming over the next 5 years so it should trade at a higher p:e ratio than the average stock and it does. Let’s lower our growth expectations a bit to 12% and see what sort of a p:e ratio we get.

Expected P:E = 20 x (1.12 ^ 5) / 1.34 = 26

How about a company that is just cruising along at the market average rate of 6% or so above inflation. Nothing exceptionally good or bad about this company. And we expect more of the same.

Expected P:E = 20 x (1.06 ^ 5) / 1.34 = 20.

Makes sense. Average company. Average growth outlook. We’d expect it’s p:e to match the market average.

What about a company that is struggling to make any headway and has seen its profits stagnate over the past few years? The expected p:e ratio would be…

Expected P:E = 20 x (1.00 ^ 5) / 1.34 = 15.

Quite legitimately, market expectations are low for this company and the p:e should reflect that. And again, it does. This struggling company is expected to trade at a p:e that is less than half that of its high growth competitor.

The actual numbers this formula spits out are going to vary a bit depending on what number you feed in for the market average p:e, so depending on how representative that market average number is, you might find that this formula seems to be consistently over or underestimating the p:e ratios you’re actually seeing. You can always tweak the market average number up or down to more closely align with the p:e ratios you’re observing. One advantage of simply using the 5 year p:e to compare stocks is that it avoids this issue altogether.

The expected p:e becomes the stock’s fair value and the degree to which the actual p:e is below the expected value is the margin of safety. Instead of looking for stocks that had the lowest 5 year p:e ratios, you could look for those trading at the biggest discount to their expected p:e. In other words, those with the biggest margins of safety.

The Taxonomy Of Growth

The numbers you feed into your value formulas obviously have a huge impact on the answers you get back out of them. An accurate growth rate assessment is an essential part of correctly valuing a company. A rapidly growing company can easily be worth twice as much or more than one that isn’t growing. Your assessment of growth matters.

But growth can be a slippery fish to get a handle on. Just as the earnings figure I use is open to interpretation and adjustment (more on that in the next chapter in this series), so too is my estimate of future growth. This is what makes investing as much of an art as it is a science. There are a lot of factors that are going to determine a company’s rate of growth over the next five years and many of them are simply unforeseeable.

Because growth can be so difficult to pigeonhole with any degree of accuracy, I often find it very helpful to conceptually divide the market up into broad growth categories, rather than try to pin my growth estimates down to the nearest percentage point. Humans excel at pattern recognition. We look for repeatable patterns to make sense of large seas of numbers. This is why I find it much more useful to think in terms of general growth categories like “no growth”, “average growth”, or “high growth” instead of in specific growth rate numbers like 2%, 6%, or 17%.

During my periodic market reviews, even after I’ve weeded out the many companies that don’t meet my basic criteria (those with too much debt, those that are unprofitable or those in sectors like mining exploration or biotech that I routinely avoid), I’m still left with a universe of close to 1000 stocks that could potentially offer an opportunity for investment. That’s an awful lot of companies to get your head around. I can’t be doing a detailed growth analysis on each and every one of those stocks or my mountain bike would never make it out of the shed, so I frequently fall back on four basic growth categories to frame the stocks I’m looking at and simply try to place each of the stocks I come across into one of those 4 broad categories.

By framing the investment universe in this way, I can turn the overwhelming complexity of the market into a much more manageable handful of menu options. It’s easy to get lost in the weeds, constructing increasingly complicated financial models on your prospective investments. By aggressively simplifying and distilling the universe of stocks down to a few basic categories I can more easily see the forest for the trees and get to the essence of the value opportunity that may or may not be presenting itself.

These are the four basic growth categories that I typically divide the universe of stocks into…

Average Growth

| Growth Category | Growth Rate Assumption | Range |

| Average Growth | 6% per year | 3 – 9% |

To qualify as average, I am looking for companies that are growing at the average historical rate of around 6% a year over inflation. At that rate, in an environment where inflation is running at 2 or 3% a year, you’d expect the company to have roughly doubled in size over the past 10 years. If you were to look back at the company’s results from 10 years previous, you should see that sales, earnings and book value were all roughly half of what they are today.

When looking at past growth rates to guide your estimates of future growth you ideally want to measure from similar points in the business cycle. Many an investor has been tripped up by measuring growth from the bottom of a recession or downturn to the top of the following cycle and then extrapolating this number forward. But measuring from the bottom will heavily skew your results.

In assessing past growth, we want to get a number that’s representative of how fast the company can grow over a full business cycle. While I’m willing to project this growth rate only 5 years into the future, that doesn’t mean that I always use the past 5 years as my guideline. I want a sense of how quickly the business is growing on average as the best guide to how quickly it might grow on average in the future.

Frequently though, you simply don’t have the data you need to make a proper assessment. The company may have gone public near the bottom of the last recession and so you don’t have the option of going back and measuring performance from a period before the downturn. Or, it may have just gone public a couple of years ago and you don’t have any long-term data at all!

This again is where it is helpful to have a few broad growth categories to fall back on. There are certain characteristics common to the compounders, or to the high growth, average growth or no growth companies. If a company looks like a duck, quacks like a duck and swims like a duck then it is probably a duck, whether or not you have the historical data to prove it or not. Failing that, my average growth bucket is my default. If I’m not sure what kind of company I’m dealing with, I assume it’s average.

Even with a full set of historical data in hand it may still be impossible to be too precise with your growth rate estimates. If sales have climbed by 8% a year over the past few years while earnings have risen by 5% and book value has climbed by 4%, then what’s the growth rate? What if earnings have grown by 8% a year over the last 10 years but more recently growth has slowed to the 5% mark? All those different growth rates could paint a very confusing picture if you were trying to nail growth down to the nearest percentage point. And they are all backward-looking. The next 5 years is likely to be somewhat different again.

You can’t possibly predict the future with any real degree of accuracy. Pretending to try is not worth the time and effort. By using the valuation formulas I outlined above, I can get as specific as I like with my projected growth rates. But much more frequently, I simply take the mid-range of whatever growth category I’ve slotted a company into and use that. Taking a step or two back, we can see that all those different growth rates I reeled off in the two paragraphs above are converging around the 6% mark, which would qualify this company as an average growth sort of situation. In fact, anything between about 3% and 9% would be sufficient to put a company into my “average growth” basket. Provided nothing significant has changed at the company recently (and that’s something I always have to be on the lookout for) then predicting a continued growth rate of 6% or so a year, for the next few years at least, would seem to be a reasonable expectation.

I always use per share numbers for my growth rate calculations to adjust for share buybacks and new share issuance. In the modern era of large and frequent share buybacks, this has become absolutely essential. As well, I’ve started adjusting all my numbers for inflation. You can download historical CPI numbers from the internet quite easily or else use an online inflation calculator. Any time period that includes the inflationary boom of the covid era is going to benefit from an inflation adjustment.

Another important thing to watch out for is a high dividend payout ratio. If a company has been dividending out most of its earnings to shareholders, it is unreasonable to expect it to also be able to reinvest in its own growth. So a high payout ratio (which measures the percent of earnings that are paid out as dividends every year) can get a company into the average growth category even if earnings appear to have flat-lined. The way I adjust for this is that I multiply the payout ratio by the market average growth rate of 6% and add that number to my observed growth rate. So if the company has been growing at 2% per year but has been paying out half of its earnings as a dividend (payout ratio 0.5), that will add 3% to my calculated growth rate, bringing it up to 5% and pushing it from the no growth category into the average growth one.

Even though their growth may be wholly unremarkable, my average growth stocks can still make wonderful investments if I can buy them at a big enough discount. In fact, this category of stock has probably made up the majority of my investments over the years. I’ll often try to tilt the odds in my favour even more by searching out those companies which may have exhibited average growth in the past but have some tricks up their sleeve which could end up surprising investors with higher growth in the future. Maybe they have a pile of cash on their balance sheet or a new product about to be introduced into the marketplace. Maybe they’ve just made a strategically important acquisition. Because the market is not expecting too much out of them, they are less likely to disappoint and may pleasantly surprise you instead.

Because of this potential, and because of the values you can often find here, I like to think of these stocks as not just average but “perfectly average”.

No Growth

| Growth Category | Growth Rate Assumption | Range |

| No Growth | 0% per year | < 3% |

Moving down the growth spectrum, I have my “no-growth” companies. These are companies that are just treading water. They don’t pay out much of a dividend so I can’t give them a pass for that. Despite their best efforts, profits have been stagnating or modestly declining for the past number of years. Maybe they are in a slowly dying industry or are struggling with a legacy product that no one wants anymore. Maybe the company is just badly run. For whatever reason, they are going nowhere fast. But every dog has its day. Sometimes they can get their act together and turn things around. Pivot into new lines of business, develop new products, hire more competent managers. If they do, the stock price can soar. I need to be able to buy in at the usual discount to make the gamble worth it, but even a dog like this has its price.

There is an important distinction to be made here between companies that are just treading water and companies that are in freefall. I try to avoid the companies in freefall or in a state of terminal decline. The companies in my no growth category are struggling, but they have not given up the fight. I need to see some hope of redemption, or I’m not interested. I try to avoid companies that are destined for the trash heap.

Another important distinction to be made is between no growth companies and companies facing a temporary setback. If earnings have temporarily dropped back down to the level they were at a few years earlier, this doesn’t necessarily make the company a no growth company. The key word is temporary. As long as I am confidant that earnings will recover back to their previous peak and then resume their steady march upwards, I won’t label that company a no growth situation. I’ll look at the company’s longer-term track record and base my growth estimate off of that. As well, I won’t use the currently depressed earnings as my baseline earnings number. I’ll go back and use an earnings figure from before the downturn began. However, if I’m not completely sure that the slowdown is just temporary or that earnings are guaranteed to fully recover, I’ll “dumb down” that baseline earnings estimate, taking an arbitrary 25% off the previous peak earnings to reflect that uncertainty.

These temporary slowdown situations are often referred to as “turnarounds”. You’ll see a lot of them during recessions. Here, the temporary nature of the earnings decline comes from the fact that recessions are also temporary events and once the economy is back on track, earnings will recover and earnings growth will likely resume.

So no growth refers to a longer term track record of weak growth, not to a disruption in growth caused by some temporary event.

I’ll often use the no growth category as my catch-all for any companies I don’t like or that come with unusual risks. For instance, companies in emerging markets often trade at a lower p:e than you’d expect, largely because of the geopolitical risk of investing in a company in a country that may not have the same rule of law or shareholder protections. As an easy method of adjusting my valuation downwards to account for this, I’ll just toss it into the no growth pile regardless of what it’s growth rate actually is.

Likewise, if a company is heavily reliant on a single customer or has a crucial patent that is set to expire in the near future, I’ll toss it into the no growth bucket. If it still shows up as undervalued at this lower valuation, then I need to take a closer look and really decide if the low price is worth the added risk. It may not be. Simply because a company shows up as undervalued by the numbers, doesn’t mean I have to take the bait and buy it. I think of it as a helpful suggestion only.

Unquestionably, the no growth category is a scary place to hang out. But there are quite a few companies out there that fall into this bucket, especially once you adjust away the effects of inflation. So there is lots to choose from in this arena. And because the stories are so unattractive, these stocks can drift down into deeply undervalued territory. Ideally, as you research these companies, you’d like to see some light at the end of the tunnel. Some reason or opportunity for the company to pull itself out of the doldrums. You need to enter this space with your eyes wide open, but if you do your due diligence there are opportunities to be had down here.

High Growth

| Growth Category | Growth Rate Assumption | Range |

| High Growth | 18% per year | > 15% |

Some companies will have a line on something more exciting. Maybe a new technology, process, brand or service that lets them grow at a significantly higher rate. There’s often something proprietary or unique about what they do. These companies can make great investments if you can find them at the right price. To qualify as a high growth company, I am looking for earnings to double (at a minimum) over the next five years. Ideally, I want to see evidence of even faster growth in the 25% or greater range over the past year or two.

While these sorts of companies rarely come cheap, occasionally you’ll find one whose growth prospects are being overlooked or under-rated by the market and you can get in at a reasonable price. If I can buy in at a significant discount then not only do I stand the chance of getting a nice ride from the p:e ratio re-rating upwards as the valuation gap closes, but I’ll also enjoy an added tailwind along the way from an increase in the underlying earnings. A higher p:e ratio on higher earnings can be a powerful combination.

Which is why investors tend to salivate over these kinds of companies. It is easy to get carried away and project rapid growth many years into the future. That’s how a lot of investors trip themselves up and end up overpaying for the latest sexy, high growth stock. Not only do I limit myself to a 5 year time horizon when projecting out future growth rates, I also put a cap on just how rapidly I expect earnings to increase over those 5 years. 18% is the number I use for my projected 5 year annual growth rate for these companies. Some companies are legitimately growing faster than that, at least in the short term, but if they are, I give them no extra credit for it. Over the years I’ve seen too many high-flying companies flame out and fall back down to earth. So I have no category for “even higher growth”. 18% is as far as I’m willing to go.

Compounders

| Growth Category | Growth Rate Assumption | Range |

| Compounder | 12% per year | 9 – 15% |

Lying in between the “average growth” segment of the market, which is where you’ll find most companies hanging out, and the relatively rare “high growth” sector, lies a segment of the market that I admittedly have never felt overly comfortable in. I call these the “compounders”. These are companies with a long track record of consistent, above average growth. To put some more specific numbers on it, let’s say somewhere around the 12% per year mark. (Range 9 – 15%.) Their success is often not due to any unique product or service but instead is simply due to consistent and efficient business execution. Often, they will have grown though a steady string of well-executed acquisitions.

If I don’t have confidence that the company can continue to outperform for at least the next 5 years, then I don’t slot it into this category; it gets bumped back down to average growth. Some investors, including a certain famous investor out in Omaha, will try to identify these perennial outperformers by the “moat” they have built around their businesses. I’ve never been able to see those supposed moats very clearly myself, but if the company has a good track record behind it and I see no obvious reason why growth would slow in the future, then I will grudgingly give it extra marks for its superior track record and valuation-wise I’ll slot it in midway between my average growth and high growth categories.

Keep It Simple

My approach to company valuation is fairly simple, especially the basic 5 year p:e calculation, compared to some of the more complicated financial modelling that professional analysts use, but that’s a strength not a failing. A basic 5 year look-ahead period, combined with my four broad growth categories, gives me just enough nuance to differentiate the market wheat from the chaff without getting too bogged down in the details. Keeping it simple provides clarity and perspective and keeps me from getting lost in the weeds.

My valuation framework may be simple, but the proper implementation of it requires a lot of research, analysis and careful decision making. There’s a lot that goes on behind the scenes. Many companies that initially appear to be undervalued don’t make it past a thorough vetting process. Initial impressions are frequently wrong. You might start your investigations with certain growth rate assumptions but later ratchet down those expectations as you find out more about the company. Conversely, the company might have hidden talents or opportunities that weren’t apparent on your initial appraisal, and these might cause you to raise your estimates. In reading through the company literature, there might be red flags that pop up, like a recent build-up of inventory or pending litigation. These softer, subjective factors are often what make or break a potential investment. My value formulas will help navigate me to the right neighbourhood, but it’s good old fashioned common sense and elbow grease that lead me to the right house.

It’s this more granular level of detail that I’ll get into next in part 5 of this series, “Hitting The Books.”